The UK political system is usually relatively stable, but it’s going through something of a crisis right now. Our parliamentary democracy is gridlocked over how to implement the result of the 2016 Brexit referendum, where a narrow majority voted in favor of the UK leaving the EU.

As the debate continues, it seems the general population has found another way to divide itself. There are those who are sick of Brexit, and those for whom the wall-to-wall media coverage is compulsive viewing.

I’ve definitely found myself in the second camp. Regardless of my own opinions on the referendum results and subsequent events, we’re witnessing something completely unprecedented in the UK. Suddenly, parliament has all the drama, complexity and unpredictable consequences of an interactive Black Mirror special.

And our graph visualizations give us a completely unique viewpoint of how that’s playing out.

Visualizing Brexit votes as a network

Our customers usually use our network visualization technology to detect fraud or prevent cyber threats, but it can help you ‘join the dots’ and uncover stories in any kind of network data. The House of Commons (the UK parliament’s lower house) for example, is one big network.

Intrigued by the idea of parliament as a network, and looking for more reasons to bore my colleagues with Brexit talk, I started visualizing Commons votes.

Note: you can click any screenshot in this post to see a larger version.

In this blog post, I’ll share some visualizations from 4 votes related to the Prime Minister’s proposed UK withdrawal agreement, showing how party politics is working – or not working – in the Brexit process so far.

The data and the visual model

The data is from data.parliament.uk, which makes available datasets covering all sorts of activities taking place in the Houses of Parliament. The Commons Divisions datasets (divisions are processes by which MPs vote) are handily provided as JSON objects, which are ready to load into our visualization products.

In the data, there are three bits of information we need to know:

- who the MPs are

- which party they’re members of

- which way they voted

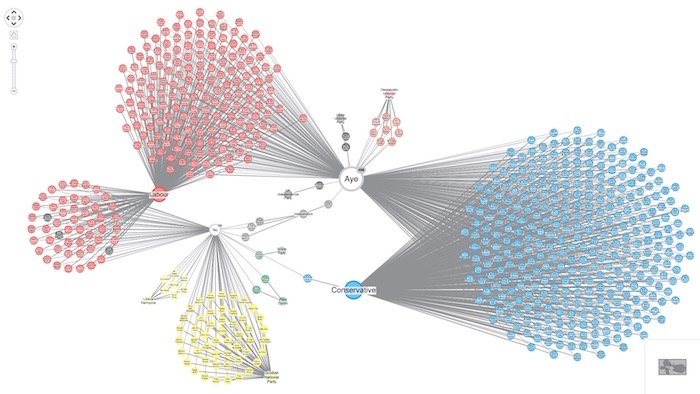

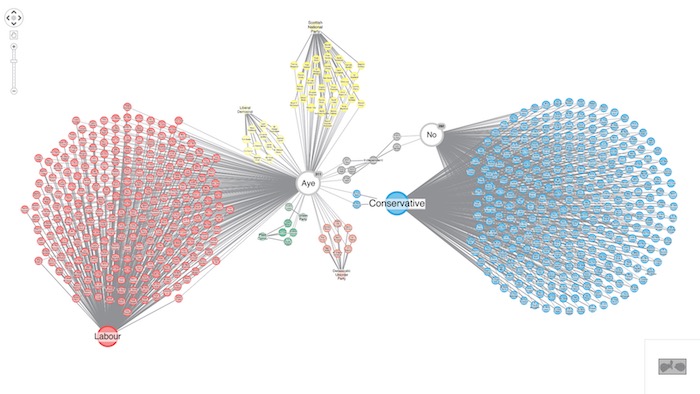

So those become our three nodes. The visual model is then clarified with coloring (using party colors), node sizing and link weighting. We also added a vote total as a glyph to make it clear which side won – Aye (Yes) or No.

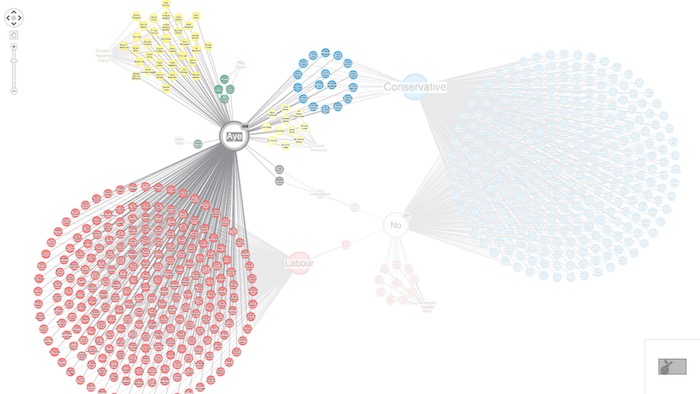

Vote 1: Dominic Grieve Amendment

We’ll start with a couple of examples from 04 December 2018 – a historic day when the government lost three votes in a single afternoon and was found in contempt of parliament.

The withdrawal agreement Theresa May had negotiated with the EU was already in trouble. Brexiteers (who want to leave) felt it gave away too much sovereignty and remainers (who want to stay) felt it was worse than the existing EU relationship.

Manoeuvering began to make sure MPs could have their say in what happens next if (let’s be honest – when) the deal was rejected. Conservative MP Dominic Grieve proposed the catchily-titled “European Union (Withdrawal) Act Amendment d”, to do just that.

Theresa May tried to rally the Conservatives and Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) to reject the amendment, while the other parties sensed weakness and encouraged their MPs to vote for it.

In a taster of what was to follow, Theresa May lost the votes of 25 Conservative rebels who voted with the Scottish National Party (SNP), Liberal Democrats, Plaid Cymru and Greens.

Visualizing these results as a graph, we can turn over 2000 rows of data into an intuitive overview of voting patterns, with the ability to dive into the details. Let’s take a look at a different vote.

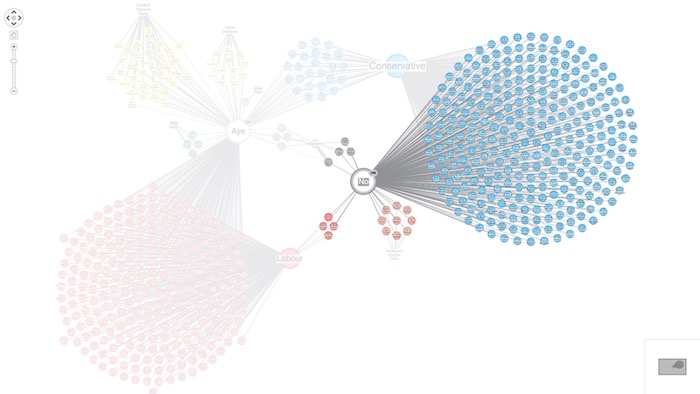

Vote 2: The Legal Advice

There was another surprising vote on 04 December. The chief legal advisor to the government, the Attorney General, had been giving legal advice on Brexit. So far, the government had only published a summary of that advice, despite repeated requests and a Commons motion ordering them to release the advice in full. Parliament was to vote on whether or not failure to release this information was an act of contempt.

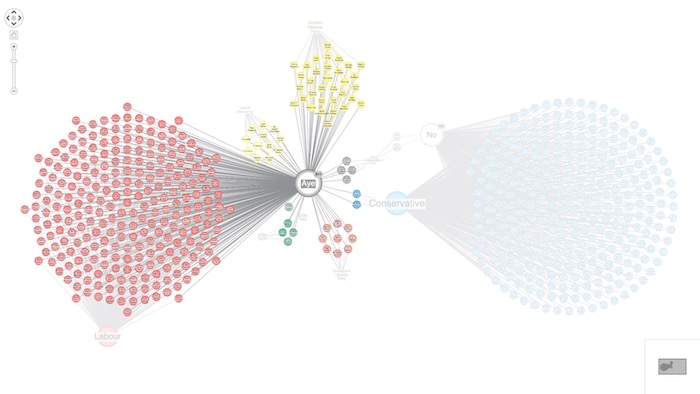

Getting ready for another division, the Conservatives galvanised support. Here’s the results:

Interestingly, the DUP decided not to support the Government on this one, despite having previously promised to back the Conservatives on motions of confidence and budgetary votes.

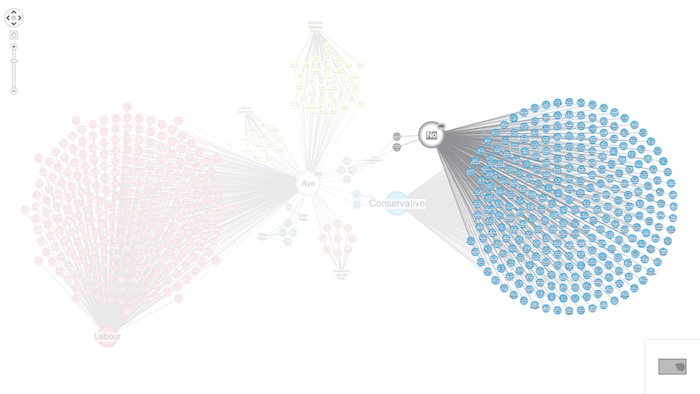

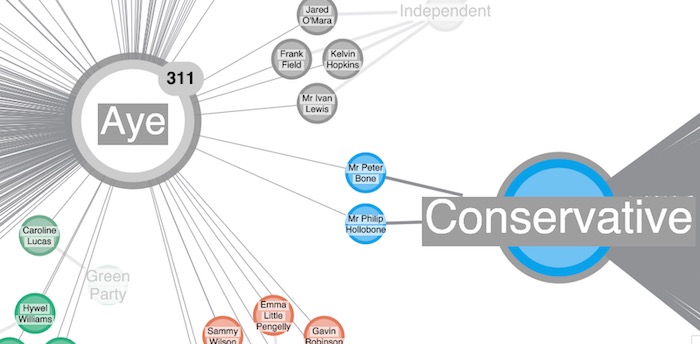

In fact, two Conservative MPs voted against their own party to find their government in contempt of parliament:

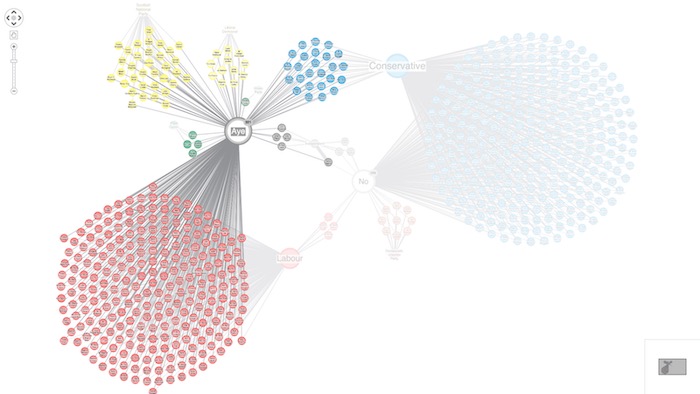

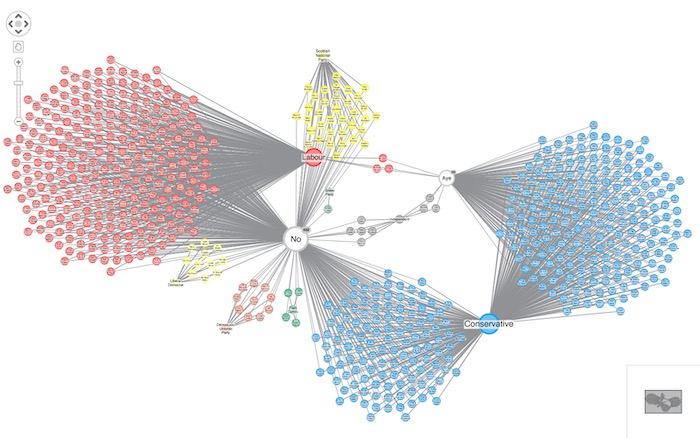

Vote 3: Dominic Grieve Returns

Let’s look at one more division.

On 11 December 2018, Parliament was due to vote on the latest withdrawal agreement – known as the ‘meaningful’ vote. When Theresa May postponed the vote until January, it raised serious concerns. Under British law, the UK must leave the EU on 29th March 2019, leading to fears that the government was ‘running down the clock’ to pressurize MPs into backing the deal.

In an attempt to prevent further delays to the process, Dominic Grieve tabled yet another amendment. This time he insisted that if the government lost its meaningful vote, it would need to present plan B to Parliament within 3 days, rather than the 21 days previously agreed.

This was remarkable because, in theory, the vote should never have happened. Only government ministers are able to amend business motions, and Grieve isn’t one of them. The Commons speaker, John Bercow, broke with precedent by allowing the vote. It caused the government a great deal of upset, especially when some from their own party rebelled, and the government lost for the 2nd time in 24 hours.

Vote 4. The meaningful one

Spoiler alert: the government lost.

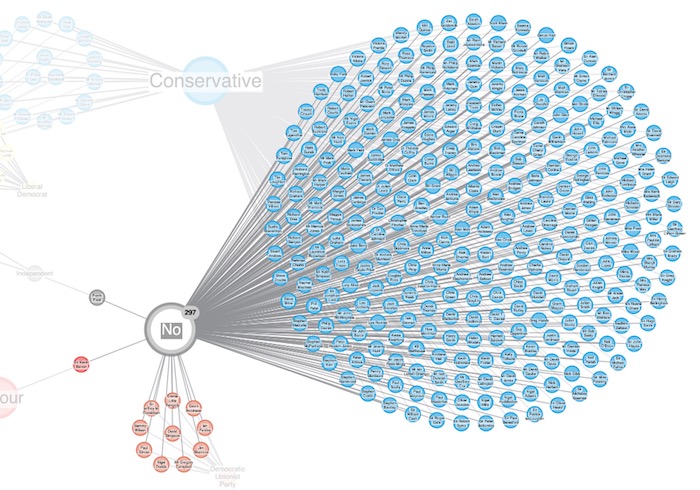

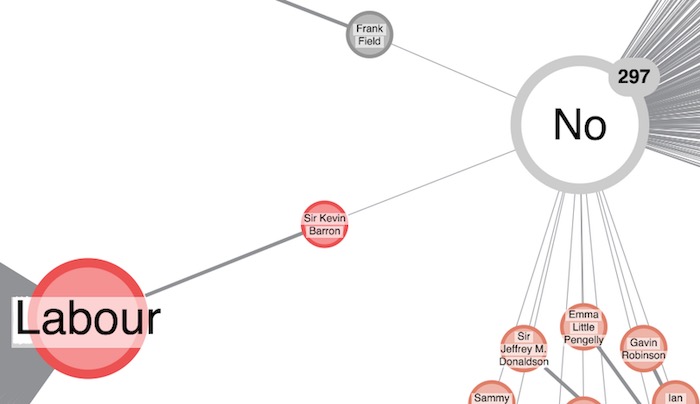

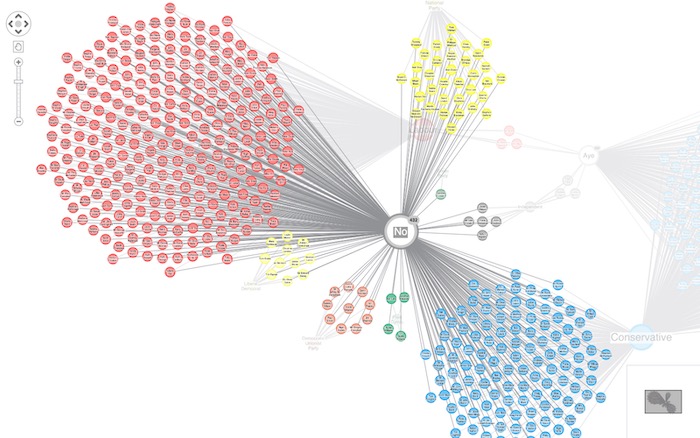

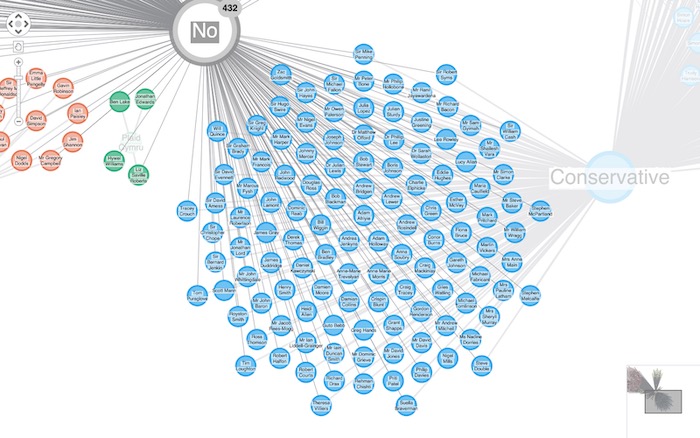

More than two and a half years after the Brexit referendum, following endless debates, resignations, protests, motions, amendments and divisions, the House of Commons voted on whether or not to approve the withdrawal agreement. The result was more spectacular than expected – one of the most resounding defeats in parliamentary history, leading to a motion of no confidence in the government.

Among the noes were the parties who had consistently been united in their opposition to the government’s Brexit policy: the Liberal Democrats, the SNP, Plaid Cymru and most of the Labour party. The DUP kept their pledge to oppose it too.

The most remarkable (although predicted) trend was the huge number of rebel Conservative MPs:

Although the scale of the defeat was huge, it really wasn’t unexpected. Throughout the process, we can see how the Conservatives have struggled to win votes as a minority government. With so many pro- and anti-Brexit MPs committed to blocking the deal, the result was unavoidable.

So what next?

Sometimes we like to use graph visualization to predict the future. But in this case, it’s probably beyond even the powers of graph theory. Personally, I’m holding out for SNP MP Patricia Gibson’s hope that a mermaid riding a unicorn ‘will happen by to provide a solution’. It seems as likely as the rest of it.

Want to try it for yourself?

In these examples, our technology made it quick and easy to build game-changing visualization tools that turn connected data into insight.

If you’d like to start your own evaluation, request a trial account of our data visualization toolkits.